Everyone has a hobby. But how about building a 50-story-high clock?

Namely, a clock costing you at least $42 million to make because you would build it in a mountain. And you'd design it so that it runs for 10,000 years using the Earth's thermal cycles.

This is the pet project of Jeff Bezos, who you probably know as the founder of Amazon.

Bezos has invested millions of dollars in the "Clock of the Long Now." It's supposed to tick once a year, while tracking each century and millennium. (A cuckoo is supposed to spring out once every millennium, by the way.)

A few, albeit smaller, prototypes exist, located in San Francisco and London. But the largest clock of them all is being built inside of a mountain in West Texas.

While a clock that counts the years might not be all that useful for the average person, we all have a "body clock" that syncs us up with what happens in our environments. Alongside this clock are multiple, peripheral clocks, constantly running to keep your organs functioning...

Circadian rhythms are the various physical, mental, and behavioral changes in your body that happen over roughly a 24-hour period. Examples of rhythms include sleep, heart rate, metabolism, temperature, hormone production, appetite, and digestion, to name a few.

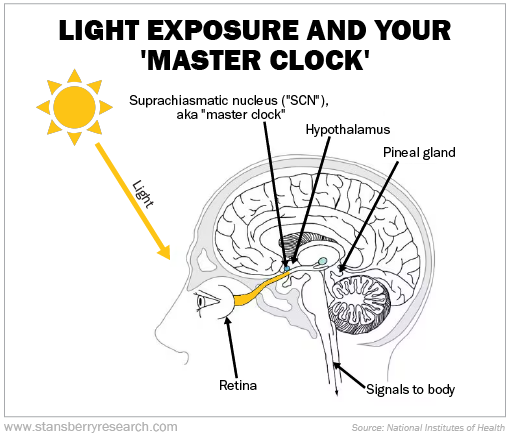

Overseeing your peripheral clocks and synchronizing them to your environment is the "pacemaker" of circadian rhythms... the suprachiasmatic nucleus ("SCN").

This "master clock" is made up of roughly 20,000 nerve cells, or neurons. And it's tucked away right in the hypothalamus. That's the center part of the brain responsible for keeping stability in your body through releasing or inhibiting hormones, as well as regulating your body temperature, appetite, and more.

There, the SCN constantly receives cues from your environment, which lets it coordinate and synchronize all of the other clocks' biological rhythms in your body.

And exposure to light affects your SCN... big time.

When light hits your eye, the thin layer of tissue at the back of the eyeball detects it. This is your retina. It has a special type of cell that contains a protein called melanopsin, which translates the light into electrical signals that zip through each optic nerve to the SCN.

From there, your SCN relays messages to parts of your brain responsible for churning out important hormones... like growth hormones, the "stress hormone" cortisol, and − perhaps most important − the "sleep hormone" melatonin, which is produced by the pineal gland.

Cortisol keeps us awake so we can go about our day. So its levels peak in the morning and are lowest during the night. With less light input received, your SCN tells your body to start pumping out some melatonin to get you ready for sleep. And melatonin levels tend to peak around 2 a.m. to 4 a.m.

But the SCN's reach goes beyond just the control of your sleep-wake cycle...

We've got social obligations to fulfill, and so we set our alarms to wake up in time. Problem is, the time on your alarm clock probably doesn't match your body's preferred wakeup time.

That time difference between your social clock and internal clock is referred to as "social" jet lag. And it works a bit like the "real" jet lag of traveling across time zones.

Roughly 70% of working adults and students experience one to two hours of social jet lag. And this lag typically happens due to the different waking times between the workweek and the weekend where you might sleep in. It's especially common among those who work jobs with nontraditional hours (like the graveyard shift, for example).

You might see symptoms like...

- Fatigue and daytime tiredness

- Depression and anxiety

- Impaired cognitive function, like having trouble concentrating

Worse, you can end up with chronic disruption of your biological clock. Numerous studies suggest that if you have chronic circadian problems, you could become a walking target for trouble that includes...

- Cardiovascular problems, like heart attack, stroke, and heart disease

- Weakened immunity, so it's harder for you to bounce back from being sick or fighting an infection

- Metabolic problems, which can lead to diabetes

Fortunately, whether it's social jet lag or jet lag from traveling, the best solution is simple...

Wake up and go to bed at the same time each day – weekends included.

Of course, a couple times a year, that advice becomes harder to follow... at the beginning and end of daylight saving time ("DST"). Leading up to the start of DST, I aim to start snoozing 10 to 15 minutes earlier than usual for a few days before we move our clocks forward by an hour.

According to a study published in July's Scientific Reports, it takes our bodies an average of eight to 12 days to get used to the end of DST in the autumn... and nine to 17 days when it begins in the spring. (Folks also typically have gentler jet lag when they're flying west to a later time zone than east into an earlier one.)

"Night owl" folks who operate best on waking and sleeping late tend to have a harder time adjusting to DST changes than the "morning larks." Naps can be a good way to cope, especially if the effects are dragging on long after the clocks change. Stick to 20-minute snoozes, tops, to avoid feeling drowsy instead of well rested upon waking.

As for what you can do year-round to keep your circadian rhythm in alignment, I shared my tip in last month's Retirement Millionaire issue. (If you're not a subscriber, get the details on a risk-free, 30-day trial right here.)

What We're Reading...

- Circadian disruption, gut microbiome changes linked to colorectal cancer progression.

- Something different: How one American tricked the enemy and freed more than 500 prisoners of war.

Here's to our health, wealth, and a great retirement,

Dr. David Eifrig and the Health & Wealth Bulletin Research Team

December 5, 2024