Doc's note: There is one indicator that has flashed a warning sign before every recession over the past 60 years...

Today, I'm sharing a Stansberry Digest issue from my colleague and co-editor of Stansberry's Credit Opportunities, Mike DiBiase. Mike details why this indicator shows we're dangerously close to a recession and what it will mean for you.

Have you ever been denied credit?

Maybe you were trying to buy something at the local hardware store and your credit card was declined. "The machine must be acting up," you might have thought to yourself.

Or maybe you've been denied a loan. It's embarrassing, and it leaves you with a sick, unpleasant feeling in your stomach.

Now imagine that you needed that loan just to stay afloat... to keep up with your bills and pay the minimum balances on your credit cards.

That's the situation facing hundreds of companies in corporate America...

Suddenly – and without warning – they'll be denied credit. The companies in the worst financial shape will have nowhere to turn for help.

When this happens, it will bring both the bond and stock markets to their knees.

Today, I will explain why this will happen – much sooner than you might think...

The stock market has marched higher without pause over the past several months, gaining back all of its late-2018 losses and then some. The S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite indexes recently hit record highs. Corporate earnings are expected to rise this year, and the economy appears healthy.

It's easy for investors to be complacent right now. But most folks are forgetting that one of the hidden forces behind this record-breaking bull market is debt.

Following the last financial crisis, corporate America deleveraged – but it didn't last long...

Since then, companies have borrowed massive amounts of money. Today, corporate America is more indebted than ever before, owing a record $9 trillion.

But these companies didn't put that money toward investing in new factories, equipment, or technologies. Instead, most borrowed money simply to buy back their own stocks.

Buybacks are the single largest source of demand for U.S. stocks. They bid up stock prices by increasing demand for shares, while at the same time reducing the supply.

This strategy has also made these same companies much more leveraged and risky.

Many are now in danger of going broke. And yet, if you turn on CNBC or read the front page of the Wall Street Journal, nobody else is talking about how dangerous this is.

Today, there are more "zombie" companies in corporate America than ever before...

A zombie company is a company that doesn't make enough money to even pay for the interest on its debt. These zombie companies are like the walking dead. They have no hope of ever paying off their debts.

The only thing keeping them alive is banks with low lending standards that are willing to extend them credit. This practice is known as "extend and pretend" because the banks are kidding themselves that the zombies will be able to pay back the principals of their loans. Without the banks rolling over (or refinancing) their debts, these companies would cease to exist.

According to a study by the Bank of International Settlements ("BIS"), the number of zombie firms has increased sixfold since the mid-1980s. The BIS estimates that one in six U.S. companies is now a zombie.

Imagine how many zombies there would be if companies had to pay reasonable interest rates... or if the economy hadn't been humming along. The number would likely be two times higher.

If banks suddenly denied credit to the zombies, a tidal wave of American companies would go bankrupt. The result would be skyrocketing default rates... massive credit losses... bond investors rushing for the exits... and the economy grinding to a halt.

"Extend and pretend" is propping up the entire U.S. economy...

This game can't go on forever. I believe its end is near.

We're getting close to a situation in which banks will be better off denying credit. Denying credit is a simple financial decision for a bank. When a bank can make more money by refusing credit than by extending a loan, it will cut off credit to the zombies.

You see, banks can still recover most of their loans when they force a company into bankruptcy. Most bank loans are secured by company assets and are senior to all other debt. That means they get paid first when a company goes bankrupt. That's why they recover far more of their investments than other creditors.

According to credit research and ratings agency Moody's, banks recover between 80% and 90% of their loans in bankruptcy. They'll gladly force a company into bankruptcy if that's more than they think they'll get by kicking the can down the road and watching the company get weaker and weaker.

But other corporate lenders further down the credit ladder – like bond investors – won't fare nearly as well. Historically, they've recovered only around $0.40 on the dollar of their investment in bankruptcy. And this time around, they'll get much less than that.

That's because the credit protections built into many types of less-senior corporate debt have deteriorated...

Covenants are rules in the credit documents that protect lenders by preventing companies from taking certain actions. Loans with weak protections are called "covenant lite."

You can judge the quality of lending standards by the covenants that govern them. And as you might guess, loan covenants have steadily weakened since the 2008 financial crisis.

The deterioration of these covenants is known as "covenant creep." As the Fed kept lowering interest rates, investors rushed into riskier, higher-yield investments... And as more dollars competed for these investments, investors threw credit protections to the wayside.

When this debt does go bad – and it will go bad – investors will be left holding the bag.

And another high-yield market is just as risky as – and even bigger than – high-yield bonds...

The leveraged loan market recently hit $1.6 trillion according to Bloomberg, double the amount at the end of 2008.

These are loans that banks make to companies with poor credit... But they're nothing like secured loans and lines of credit that sit atop the credit ladder.

They're more like high-yield – or "junk" – bonds. Investors like these loans because of their floating interest rates. As interest rates rise, these loans pay more interest.

You might be wondering what all of this has to do with you...

It turns out, you might own some of these leveraged loans without even realizing it.

You see, banks don't hold on to these risky loans for long. These loans – called collateralized loan obligations ("CLOs") – get packaged up and sold to institutional investors like pension funds, hedge funds, and mutual funds.

What's troubling is that there is no direct oversight of the leveraged loan market.

Yield-hungry investors have been snatching up these loans in droves, ignoring the similarities to the subprime mortgages that triggered the last financial crisis.

The risk of leveraged loans has grown faster than high-yield bonds...

The number of covenant-lite leveraged loans has soared... Today, more than 85% of leveraged loans are considered covenant-lite, up from just 17% in 2007.

Former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen sounded the alarm on leveraged loans last October. She's worried about "the systemic risk associated with these loans."

How soon could this all blow up?

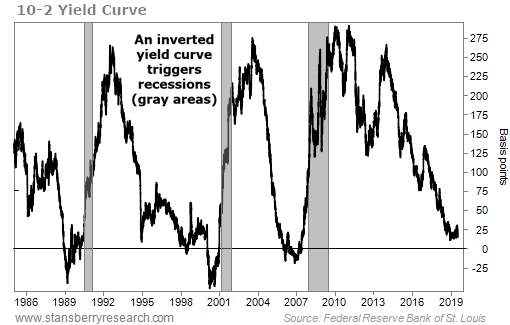

To know the answer to that question, pay close attention to the so-called "yield curve" – the difference between long- and short-term interest rates.

Most of the time, long-term rates are higher to compensate for the trouble of tying up your money for longer durations. But when that relationship flip-flops, the yield curve is said to have "inverted."

You can measure the yield curve in a number of ways. The most common is the "10-2 yield curve" – the difference between rates on 10-year U.S. Treasurys (which yield 2.06%) and two-year Treasurys (which yield 1.83%). The difference is just 23 basis points (0.23%) right now. In other words, the yield curve is extremely close to inverting.

That doesn't happen often, but when it does, it spells trouble. An inverted yield curve preceded the past seven recessions. You can see the latest three instances in this chart...

When the yield curve inverts, banks tighten credit...

Banks borrow money at shorter-term rates and lend money at longer-term rates. So when the yield curve inverts, they're forced to pay more in interest than they're able to charge for their loans. So they issue far fewer loans... and zombie companies that rely on banks to refinance their debt suddenly get cut off and go bankrupt.

The last time we saw this was in 2006. Before that, banks had been loosening credit. After the yield curve inverted, they immediately began tightening. By 2008, more than half of all banks were tightening. Credit dried up and kicked off the last financial crisis.

Every quarter, the Federal Reserve conducts a survey to determine whether banks are tightening or loosening credit.

Earlier this year, banks began to tighten again for the first time since 2015...

Back then, the yield curve stood at 145 basis points. Banks tightened credit when oil prices collapsed, but quickly loosened it once again as prices recovered.

But this time, the yield curve is dangerously close to inverting. Some other yield curves (like the 10-year Treasurys versus the three-month Treasurys) have already inverted.

The next Fed survey should come out soon. Pay close attention to this report. If banks continue to tighten, I believe it will trigger the next financial crisis.

The possibility of the Fed cutting rates may be enough to cause banks to begin loosening credit again. That just means they'll continue kicking the can down the road a bit longer. But please don't ignore these risks...

Corporate borrowing has been far, far overdone. Many companies are so overleveraged now that they're on the verge of collapsing. Banks can't turn their backs on the risks forever.

The next crisis will begin in less-regulated markets like leveraged loans, where we've seen crazy rates of growth... then will quickly spread to the high-yield corporate bond market... and then into the stock market. Share prices of highly leveraged companies considered safe today will crash.

We're not there yet...

But make no mistake, a crisis is coming. It could be far worse than what we saw in 2008. And if you wait until the signs are obvious to take shelter, it will already be too late.

Before that happens, there are still some tremendous money-making opportunities available. To show you just how lucrative it can be, we've teamed up with one of my longtime subscribers. And as part of the deal, we've agreed to offer Stansberry's Credit Opportunities at its lowest price ever. Get the details right here.

Regards,

Mike DiBiase